EPIDEMIOLOGY OF LANDMINE INJURIES

Adam L. Kushner, MD, MPH

“landmines are a unique and malignant threat to whole societies.” Dr. Boutros Boutros-Gali, former U.N. Secretary-

General.

Alternatively referred to as ‘hidden killers” or “as a weapon of mass destruction in slow motion,” landmines constitute

a massive threat to millions of civilians and military personnel worldwide. Current estimates indicate that over 60 million

landmines litter 70 countries and contribute to the death or injury of one person every 22 minutes. The costs of caring

for victims of landmines from both a medical and public health perspective are staggering. The advantage of these

weapons from a military point of view has also recently been debated and currently over 135 nations have signed an

international agreement banning the use, stockpiling and transfer of APL. From a military medicine perspective, an

understanding of the various types, effects, and uses of these weapons is necessary to adequately prevent and care for

injuries which will almost certainly be a part of any military deployment.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The NATO definition of a mine is an explosive or other material, normally encased, designed to destroy or damage

vehicles, boats, or aircraft, or designed to wound, kill or otherwise incapacitate personnel. It may be detonated by the

action of its target, the passage of time, or by controlled means. (Figure 1) For the purposes of this review, mines

placed in bodies of water specifically used against ships will not be included. Widespread use of landmines did not

occur until World War II, however, as early as the Civil War, weapons described as “land torpedoes” were used to

restrict military troop movement. Weapon systems were advanced during the Korean War, and later in Vietnam

remotely delivered mines or scatterables were dropped in such large quantities that U.S. pilots referred to them as

“garbage.” Beginning in the 1970’s many third world nations and guerrilla forces utilized landmines because they were

cheap, durable, easy to transport and effective; they were described by Cambodian soldiers and guerrillas as “eternal

sentinels.” The Soviet 40th Army used millions of landmines during the war in Afghanistan, including “butterfly” mines

spread from the air that contribute to the large number of injuries to children who mistakenly view these devices as toys.

Figure 1: Mechanism for detonation of landmines

Initially designed to protect anti-tank mines from tampering during World War II, APL were increasingly designed

and used to injure soldiers and terrorize civilian communities. According to LTC (Ret) Lester W. Grau in the Army

Medical Department Journal, “countering mines increases the logistics burden of a force, from the simple need to deploy

the needed mine-clearing equipment and personnel, to the added medical and mortuary services. Mines that wound

rather than kill are more effective since every wounded mine casualty ties up many support and medical personnel.”

One argument against the use of these weapons is that while they pose a deadly threat to military forces, they continue

to threaten civilian populations long after the formal cessation of hostilities.

The engineers may admire their efficiency and the commanding general may appreciate the principles of their

employment, but the fact remains that those who know them (landmines) best hate them with a passion. The

unexpectedness of their damage, the high percentage of lost limbs, their tendency to strike at friend and foe alike, and

their limiting effect on the Marines’ time-honored offensive tactics-all these add up to make it the stepchild at the family

reunion.

Combat experience has taught many veterans that APL are of dubious military utility and likely to inflict a deadly

“blow-back effect,” harming the very soldiers that they are meant to defend. In Korea and Vietnam for example, the

main source of supply for mines for those fighting U.S. Forces was captured U.S. mine stockpiles. In Korea, more U.S.

casualties resulted from defensive minefields than were caused by mines encountered in offensive and pursuit

operations against the enemy. In Vietnam, the U.S. Army estimated that ninety percent of the mines and booby traps

used against its troops were either U.S. made or were made with U.S. parts. Since 1942 nearly 100,000 U.S. Army

personnel have been killed or injured by landmines.

Most recent studies have concentrated on the high percentage of civilian injuries resulting from landmines. , ,

As these weapons do not distinguish between friend or foe, soldier or child, many innocent victims have been killed

or injured. To deal with these devastating effects, vast resources must be expended as it is estimated to cost from US$

300 to 1,000 to clear a single mine. In addition, the economic and health losses due to their use, especially in the third

world, are enormous, with refugees and internally displaced persons the ones most at risk.

TYPES OF MINES

Mines vary in size, cost and destructive capacity. They can be mass-produced and cost as little as US$ 3 although

some of the more sophisticated mines may cost almost US$ 100. Of the nearly 350 types of landmines, formerly

produced in 54 countries and now in only 16, there are two major classifications: blast and fragmentation. Blast mines

are the most common APL. They are designed to be triggered by the foot of a soldier, traumatically amputating the

lower limb and propelling portions of the shoe or boot, dirt and bone higher up into the leg. Smaller APL contain from 50

to 300 grams of explosive and can not distinguish between a soldier or a civilian. American M14 mines contain 100

grams of explosive and are often called “toe poppers” based upon their effect. Butterfly mines, used by the Soviets in

Afghanistan explode when compressed and PNM mines, common throughout Eastern Europe detonate when stepped

on.

Some of these mines are fitted with anti-handling devices to slow up the demining process. For example the PMN 2

mine (former Soviet Union) has an anti-handling device that makes it impossible to detonate by using a sharp hard

strike, like the action of the 'Flail' demining machine. Detonation of a PMN 2 mine requires slow even pressure on the

top as when stepped upon. Another type of anti-handling device found in the type 72 Bravo mine (China) causes it to

explode if the mine is tilted more than 10 degrees.

Fragmentation mines are commonly composed of metal casings designed to rupture into fragments upon detonation

or contain steel balls or fragments that are turned into lethal projectiles. Either a trip-wire or pressure detonates them.

The “Bouncing Betty” or bounding mine has a small charge that propels a larger munition three feet into the air before a

second charge sends fragments in a 360-degree arc up to 100 meters. Claymore mines are considered fragmentation

mines when they are used with a trip wire. They contain 682 grams of explosive and send 700 metal spheres up to 50

meters.

Devices designed, constructed or adapted to kill or injure unexpectedly when a person or object disturbs or

approaches an apparently safe object or performs an apparently safe act are termed Booby Traps. Such weapons

explode upon opening a door, moving an object or even picking up a toy. Improvised Explosive Devices (IED) are locally

made devices often associated with booby traps that function as mass produced mines. These types of weapons have

the same function at APL and require similar treatment strategies.

Unexploded Ordinance (UXO), including missiles, rockets, grenades, cluster bombs and other explosives that fail to

explode can also act in a similar fashion as APL. Most of these devices may still be “alive” or active years or even

decades after being released. As is the case in Laos, there may be hundreds of unexploded trajectory weapons lying in

fields and forests, seemingly innocuous until handled. Unexploded cluster bombs in Kosovo are one of the threats to

NATO forces and civilians alike.

LOCATION OF LANDMINES

“In many of the poorest countries of the developing world mines are not merely instrumental in denying vital land to

farmers, pastoralists and returning refugees, but have covered large tracts of the earth’s surface with non-

biodegradable and toxic garbage.” This feeling is held by many of the people living in mine affected regions and those

working toward an international ban of APL. These weapons seriously impact on entire regions and whole segments of

the population.

It is common in many conflicts for key elements of the national infrastructure to be mined by both sides to the

conflict. Roads, power lines, electric plants, irrigation systems, water plants, dams and industrial plants are often mined

during civil conflicts. In the aftermath of those conflicts, it is often impossible to approach such facilities to repair them or

to conduct needed maintenance. As a consequence, the delivery of electricity and water becomes more sporadic and

often ceases in heavily mined areas. Irrigation systems become unusable, with consequent effects on agricultural

production. Transportation of goods and services is halted on mined roads and the roads themselves begin to

deteriorate. Local businesses, unable to obtain supplies or ship products, cease operation. Unemployment in those

areas increase and the prices for scarce good tends to enter an inflationary spiral, increasing the cycle of misery. In

those areas dependent upon outside aid for sustenance, the mining of roads can mean a sentence to death by

starvation.”

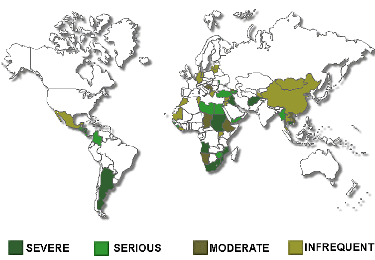

The U.S. State Department released a report in late 1998 documenting that landmines affect almost 70 counties, but

revising the estimated number of landmines in the ground from 100 million to 60 million. (Figure 3) “From the

perspective of mine action (the process whereby mines are removed), the actual number of mines in the ground is not

the most important factor… the number of minefields, their size and the type of areas affected, and the number of

people affected are actually more important. A far more important question is the number of people affected by the

landmine threat in their daily lives.” In 1996 Norwegian People’s Aid (a Norwegian base non-governmental organization

involved in demining) cleared a village in Mozambique after it had to be abandoned by the entire population of around

10,000 villagers due to alleged mine infestation. After three months of work, the deminers found only four mines. It was,

however, the perception of landmines and not the actual number that had denied access to land and caused the

migration of 10,000 people.”

Figure 2: Global distribution and severity of landmines.

In addition to landmines that are planted in the ground there are numerous stockpiles around the world. Landmine

Monitor estimated that more than 250 million APL are stored in 108 countries; the leaders are China (110 million),

Russia (60-70 million), Belarus (tens of millions), U.S. (11 million), Ukraine (10 million), Italy (7 million) and India (4-5

million).

LANDMINE INJURIES

Landmine injuries are frequently fatal. A household survey conducted in Mozambique estimated the case fatality

rate for landmine injuries at 48%, much higher than originally estimated from looking solely at hospital data. The

disability caused by these weapons is very significant, with exceedingly high amputation rates in many countries. (Table

1) UN estimates have figured that it will cost an amputee US$ 3,000 over their lifetime for prosthetics and medical care.

Country Amputation Rate per population

Cambodia 1 per 236

Angola 1 per 470

Somalia 1 per 650

Uganda 1 per 1000

Vietnam 1 per 1250

Mozambique 1 per 1862

United States 1 per 22,000

Table 1: Amputation rates for mine affected countries and the United States.

According to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), those at highest risk of mine injury are the rural

poor. Peasants foraging for firewood and food, herding cattle, or tilling their fields are particularly at risk. Similarly,

when refugees and internally displaced persons return home at random and not as organized groups, they are at risk of

being killed or maimed from landmines because they return to areas that often have been involved in fierce fighting and

may therefore be heavily mined. They are also at high risk because they are less familiar with their former ”changed”

environment. In the case of some countries, young men and women return who were born in refugee camps and have

never seen their parents’ land before.

The ICRC has documented three patterns of landmine injuries based on data collected from multiple wars and

thousands of patients. Pattern I, usually the most severe on presentation, occurs after a person steps on a buried

APL. The injury usually produces a traumatic amputation with severe wounding of the contralateral leg, genitalia and

arms. The blast is associated with proximal muscle damage and secondary contamination with mud, bone, plant

material, plastic or metal fragments, and bits of clothing or shoes. (Figure 4) The level of damage depends upon the

amount of explosive and the size of the victim. Bilateral amputations have been reported in 5% to 10% of incidents and

orchiectomies in 1% to 2%. Of 720 patients with landmine related injuries seen at one ICRC hospital, pattern I injuries

accounted for 28% of patients.

Figure 4: Pattern I injury (ICRC)

Pattern 2 relates to injuries usually sustained from a fragmentation or anti-tank mine. The mechanism that

produces this injury pattern is similar to that of other fragmentation and shrapnel type weapons. These wounds can

effect any part of the body and patients frequently require intra-abdominal exploration for bowel injuries. These wounds

accounted for 50% of ICRC patients. Pattern 3 consists of wounds sustained while handling a mine either by a demining

worker or more frequently by children playing with small mines. These wounds cause injury to the hands and face, and

frequently cause blindness secondary to the blast.

A study on civilian landmine injuries in Sri Lanka found an incidence rate of 72 per 100,000, similar to the 50-120

per 100,000 from Mozambique and much higher than the 10 per 100,000 in Kosovo. Landmine injuries have also

been responsible for many wartime casualties. These weapons accounted for 30% to 40% of the trauma cases treated

by Soviet medical personnel during the war in Afghanistan. During the Vietnam War, 33% of all U.S. casualties and

28% of all deaths were officially attributed to mines.

In a household survey in Mozambique, Aschiero calculated a case fatality rate of 48% for landmine injuries. In Sri

Lanka, Meade reported a rate of 29%, 80% of whom were dead on arrival to the hospital. A study by Anderson, et al

calculated a case fatality rate of 30%, with 75% of those deaths occurring in the field. These figures are all significantly

higher than the hospital mortality rate of 3.2% reported by the ICRC from the war injury database. The difference in

rates can be explained due to the long transport time for patients going to ICRC hospitals and the fact that data on

victims who died in route were not recorded. In Mozambique the data included all injuries from a community sample and

the Sri Lankan study was undertaken in a limited catchement area where most victims were probably taken to a hospital.

Data from the ICRC studies shows that amputations occur in approximately 23-30% of landmine victims, however

amputation rates as high as 75%, 93% and 100% have been recorded in series from Afghanistan, Thailand and

Guantanamo Bay. Variations in the percentage of above versus below knee amputations have also been documented,

although the bilateral amputation rate seems fairly consistent. These rates may reflect a difference in treatment or other

variables including transport time or types of mines. Of interest, data from Thailand showed that victims wearing boots

had significantly higher amputation levels than those wearing sandals or sneakers, the boots may have transmitted the

explosive force further up the injured limb. All the studies showed that landmine victims on average require more

operations to care for their wounds and are at a high risk of needing multiple blood transfusions when compared to

victims of other war injuries.

Landmine victims are predominantly young males. When studies of civilian injuries are compared to those of military

casualties, not surprisingly, a greater percentage of women and children are included in the data.

The majority of landmine incidents occur to groups with more than one person injured at a time. Injuries and death

result from multiple missile fragments, the use of anti-tank mines that can destroy a vehicle with many persons or the

placement of multiple landmines in a confined area or trail. For example, in one incident from the Korean War described

by Captain Edward R. Hindman, “a divisional unit of company size was moving into (an) area when one man tripped a

Bouncing Betty. Immediately two other men rushed to his aid, and one of them tripped another mine, killing himself and

wounding the other. Other personnel tried to get to the wounded men, and more mines were set off. In a ghastly

debacle that lasted only a few short minutes, a total of sixteen men were killed and wounded by our own mines.”

Such scenarios have been played out repeatedly both with military and civilian victims. Minefields are designed to

place mines in a pattern that will inflict maximum damage. During conflicts, minefields are supposed to be mapped so

that afterwards they can be marked and cleared. However, maps are not always kept or accurate and minefields are not

always marked. The use of scatterable mines also complicates removal, as the exact location of the mines is difficult to

ascertain.

In addition to the physical injuries caused by landmines there are many indirect effects. According to Anderson,

between 25% and 87% of households in Afghanistan, Mozambique, Bosnia and Cambodia had daily activities affected

by landmines. The mere presence of a minefield can prevent access to safe drinking water, leading to an increase in

intestinal diseases, diarrhea and death. Landmines can also worsen iodine deficiency disorders in villages located in

iodine deficient areas by preventing access to food being transported in from iodine sufficient areas. The inability to

conduct vaccination or public health campaigns using mobile teams has also led to increasing rates of polio and

worsening health.

Landmine injuries themselves place an enormous burden on local communities. A mother killed or disabled by a

landmine is often unable to provide for her family, a child injured by a landmine often becomes a burden on its family,

health services and society in general. Countries most effected by landmines have also generally had their medical

infrastructure severely damaged by war. Landmine injuries require skilled surgeons, large amounts of blood, antibiotics,

prosthetic devices, and intensive physical therapy. A study of patterns of hospital utilization show that even if only 4% of

a hospital's admissions are landmine victims, they tend to utilize 25% of all surgical services and resources. In a

country where resources are already scarce, caring for landmine victims draws resources from other essential health

services and tends to worsen the health status of the entire population.

Loss of livestock is also another important aspect in mine affected regions that effects both the economic and

nutritional status of the population. In Libya between 1940 and 1980, an estimated 125,000 camels, sheep, goats and

cattle were killed due to landmines remaining from World War II. In Afghanistan 264,000 goats and sheep were

reportedly lost at a value of US$ 31.6 million. Anderson’s study recorded 54,554 animals killed representing a value of

US$ 6.5 million.

TREATMENT OF LANDMINE INJURIES

Victims and survivors of landmine injuries need to be transferred to sites where appropriate and safe definitive

treatment can be undertaken. Studies have shown that the number of trained surgeons in many developing countries is

limited and have indicated the danger of attempted treatment by unskilled practitioners. Data from the ICRC shows that

only 24.6% of landmine injured patients present to a hospital within 6 hours, with 70% presenting within 24 hours and

16% arriving more that three days after injury. These data help explain the relatively low hospital mortality of 3.2%, as

the sickest patients never arrive for definitive treatment.

These figures highlight the massive problem with transportation to medical facilities; however, they also underscore

the importance of resuscitation and transfer for definitive care. Much of the recent literature concerning the

management of war-related injuries presumes that modern and well-equipped facilities are available after rapid

transport. This assumption does not apply in many countries where forgotten landmines continue to menace the local

population. While rapid definitive therapy may improve the ultimate outcome, this is rarely an option. Sound surgical

judgement along with proper wound management will provide the best outcome; however, this is only possible if the

patient reaches the hospital alive.

The United Nations Mine Action Service has developed international standards for humanitarian mine clearance

operations. The purpose of this document is “to establish medical support standards for rapid resuscitation and

stabilization of the casualty and the prompt evacuation to a facility where emergency surgery can be undertaken.” This

document presumes that mine-clearing teams have access to rapid transportation and first aid medical assistance.

Most civilian victims of landmines do not have access to such luxuries. It is therefore necessary for local districts to

establish the means for providing adequate first aid and transportation to definitive care facilities.

PUBLIC HEALTH ISSUES AND THE FUTURE

In 1995 the General Assembly of the World Health Organization recognized that landmines were a worldwide public

health concern. Krug, et al outlined the need to address this problem from a public health perspective. Such a plan

would first determine the magnitude, scope and characteristics of the problem. The factors that increase the risk of

disease, injury or disability could then be studied to determine which were potentially modifiable. By using the

information about causes and risk factors, an assessment could then be done to prevent the problem by designing, pilot

testing and evaluating interventions. The most promising interventions could then be implemented on a broad scale.

Such interventions are already underway. Coordinating bodies such as UNMAS and the Geneva International Center

for Humanitarian Demining have begun a coordinated method of data collection on mine-affected countries and injuries.

Work by WHO and non-governmental organizations has been important in developing and pilot testing surveillance

systems in Uganda, Azerbaijan and Kosovo. Initial goals of improving data collection and providing a method to

document changes in incidents and relief for survivors is slowly progressing. The international community continues to

recognize the massive losses caused by these weapons. Many nations, with the United States as the leader, continue

to contribute millions of dollars to demining efforts and for victim assistance around the world. Only through prevention

and understanding will a coordinated effort be able to care for the thousands of landmine victims each year.

Adam L. Kushner, MD, MPH

“landmines are a unique and malignant threat to whole societies.” Dr. Boutros Boutros-Gali, former U.N. Secretary-

General.

Alternatively referred to as ‘hidden killers” or “as a weapon of mass destruction in slow motion,” landmines constitute

a massive threat to millions of civilians and military personnel worldwide. Current estimates indicate that over 60 million

landmines litter 70 countries and contribute to the death or injury of one person every 22 minutes. The costs of caring

for victims of landmines from both a medical and public health perspective are staggering. The advantage of these

weapons from a military point of view has also recently been debated and currently over 135 nations have signed an

international agreement banning the use, stockpiling and transfer of APL. From a military medicine perspective, an

understanding of the various types, effects, and uses of these weapons is necessary to adequately prevent and care for

injuries which will almost certainly be a part of any military deployment.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The NATO definition of a mine is an explosive or other material, normally encased, designed to destroy or damage

vehicles, boats, or aircraft, or designed to wound, kill or otherwise incapacitate personnel. It may be detonated by the

action of its target, the passage of time, or by controlled means. (Figure 1) For the purposes of this review, mines

placed in bodies of water specifically used against ships will not be included. Widespread use of landmines did not

occur until World War II, however, as early as the Civil War, weapons described as “land torpedoes” were used to

restrict military troop movement. Weapon systems were advanced during the Korean War, and later in Vietnam

remotely delivered mines or scatterables were dropped in such large quantities that U.S. pilots referred to them as

“garbage.” Beginning in the 1970’s many third world nations and guerrilla forces utilized landmines because they were

cheap, durable, easy to transport and effective; they were described by Cambodian soldiers and guerrillas as “eternal

sentinels.” The Soviet 40th Army used millions of landmines during the war in Afghanistan, including “butterfly” mines

spread from the air that contribute to the large number of injuries to children who mistakenly view these devices as toys.

Figure 1: Mechanism for detonation of landmines

Initially designed to protect anti-tank mines from tampering during World War II, APL were increasingly designed

and used to injure soldiers and terrorize civilian communities. According to LTC (Ret) Lester W. Grau in the Army

Medical Department Journal, “countering mines increases the logistics burden of a force, from the simple need to deploy

the needed mine-clearing equipment and personnel, to the added medical and mortuary services. Mines that wound

rather than kill are more effective since every wounded mine casualty ties up many support and medical personnel.”

One argument against the use of these weapons is that while they pose a deadly threat to military forces, they continue

to threaten civilian populations long after the formal cessation of hostilities.

The engineers may admire their efficiency and the commanding general may appreciate the principles of their

employment, but the fact remains that those who know them (landmines) best hate them with a passion. The

unexpectedness of their damage, the high percentage of lost limbs, their tendency to strike at friend and foe alike, and

their limiting effect on the Marines’ time-honored offensive tactics-all these add up to make it the stepchild at the family

reunion.

Combat experience has taught many veterans that APL are of dubious military utility and likely to inflict a deadly

“blow-back effect,” harming the very soldiers that they are meant to defend. In Korea and Vietnam for example, the

main source of supply for mines for those fighting U.S. Forces was captured U.S. mine stockpiles. In Korea, more U.S.

casualties resulted from defensive minefields than were caused by mines encountered in offensive and pursuit

operations against the enemy. In Vietnam, the U.S. Army estimated that ninety percent of the mines and booby traps

used against its troops were either U.S. made or were made with U.S. parts. Since 1942 nearly 100,000 U.S. Army

personnel have been killed or injured by landmines.

Most recent studies have concentrated on the high percentage of civilian injuries resulting from landmines. , ,

As these weapons do not distinguish between friend or foe, soldier or child, many innocent victims have been killed

or injured. To deal with these devastating effects, vast resources must be expended as it is estimated to cost from US$

300 to 1,000 to clear a single mine. In addition, the economic and health losses due to their use, especially in the third

world, are enormous, with refugees and internally displaced persons the ones most at risk.

TYPES OF MINES

Mines vary in size, cost and destructive capacity. They can be mass-produced and cost as little as US$ 3 although

some of the more sophisticated mines may cost almost US$ 100. Of the nearly 350 types of landmines, formerly

produced in 54 countries and now in only 16, there are two major classifications: blast and fragmentation. Blast mines

are the most common APL. They are designed to be triggered by the foot of a soldier, traumatically amputating the

lower limb and propelling portions of the shoe or boot, dirt and bone higher up into the leg. Smaller APL contain from 50

to 300 grams of explosive and can not distinguish between a soldier or a civilian. American M14 mines contain 100

grams of explosive and are often called “toe poppers” based upon their effect. Butterfly mines, used by the Soviets in

Afghanistan explode when compressed and PNM mines, common throughout Eastern Europe detonate when stepped

on.

Some of these mines are fitted with anti-handling devices to slow up the demining process. For example the PMN 2

mine (former Soviet Union) has an anti-handling device that makes it impossible to detonate by using a sharp hard

strike, like the action of the 'Flail' demining machine. Detonation of a PMN 2 mine requires slow even pressure on the

top as when stepped upon. Another type of anti-handling device found in the type 72 Bravo mine (China) causes it to

explode if the mine is tilted more than 10 degrees.

Fragmentation mines are commonly composed of metal casings designed to rupture into fragments upon detonation

or contain steel balls or fragments that are turned into lethal projectiles. Either a trip-wire or pressure detonates them.

The “Bouncing Betty” or bounding mine has a small charge that propels a larger munition three feet into the air before a

second charge sends fragments in a 360-degree arc up to 100 meters. Claymore mines are considered fragmentation

mines when they are used with a trip wire. They contain 682 grams of explosive and send 700 metal spheres up to 50

meters.

Devices designed, constructed or adapted to kill or injure unexpectedly when a person or object disturbs or

approaches an apparently safe object or performs an apparently safe act are termed Booby Traps. Such weapons

explode upon opening a door, moving an object or even picking up a toy. Improvised Explosive Devices (IED) are locally

made devices often associated with booby traps that function as mass produced mines. These types of weapons have

the same function at APL and require similar treatment strategies.

Unexploded Ordinance (UXO), including missiles, rockets, grenades, cluster bombs and other explosives that fail to

explode can also act in a similar fashion as APL. Most of these devices may still be “alive” or active years or even

decades after being released. As is the case in Laos, there may be hundreds of unexploded trajectory weapons lying in

fields and forests, seemingly innocuous until handled. Unexploded cluster bombs in Kosovo are one of the threats to

NATO forces and civilians alike.

LOCATION OF LANDMINES

“In many of the poorest countries of the developing world mines are not merely instrumental in denying vital land to

farmers, pastoralists and returning refugees, but have covered large tracts of the earth’s surface with non-

biodegradable and toxic garbage.” This feeling is held by many of the people living in mine affected regions and those

working toward an international ban of APL. These weapons seriously impact on entire regions and whole segments of

the population.

It is common in many conflicts for key elements of the national infrastructure to be mined by both sides to the

conflict. Roads, power lines, electric plants, irrigation systems, water plants, dams and industrial plants are often mined

during civil conflicts. In the aftermath of those conflicts, it is often impossible to approach such facilities to repair them or

to conduct needed maintenance. As a consequence, the delivery of electricity and water becomes more sporadic and

often ceases in heavily mined areas. Irrigation systems become unusable, with consequent effects on agricultural

production. Transportation of goods and services is halted on mined roads and the roads themselves begin to

deteriorate. Local businesses, unable to obtain supplies or ship products, cease operation. Unemployment in those

areas increase and the prices for scarce good tends to enter an inflationary spiral, increasing the cycle of misery. In

those areas dependent upon outside aid for sustenance, the mining of roads can mean a sentence to death by

starvation.”

The U.S. State Department released a report in late 1998 documenting that landmines affect almost 70 counties, but

revising the estimated number of landmines in the ground from 100 million to 60 million. (Figure 3) “From the

perspective of mine action (the process whereby mines are removed), the actual number of mines in the ground is not

the most important factor… the number of minefields, their size and the type of areas affected, and the number of

people affected are actually more important. A far more important question is the number of people affected by the

landmine threat in their daily lives.” In 1996 Norwegian People’s Aid (a Norwegian base non-governmental organization

involved in demining) cleared a village in Mozambique after it had to be abandoned by the entire population of around

10,000 villagers due to alleged mine infestation. After three months of work, the deminers found only four mines. It was,

however, the perception of landmines and not the actual number that had denied access to land and caused the

migration of 10,000 people.”

Figure 2: Global distribution and severity of landmines.

In addition to landmines that are planted in the ground there are numerous stockpiles around the world. Landmine

Monitor estimated that more than 250 million APL are stored in 108 countries; the leaders are China (110 million),

Russia (60-70 million), Belarus (tens of millions), U.S. (11 million), Ukraine (10 million), Italy (7 million) and India (4-5

million).

LANDMINE INJURIES

Landmine injuries are frequently fatal. A household survey conducted in Mozambique estimated the case fatality

rate for landmine injuries at 48%, much higher than originally estimated from looking solely at hospital data. The

disability caused by these weapons is very significant, with exceedingly high amputation rates in many countries. (Table

1) UN estimates have figured that it will cost an amputee US$ 3,000 over their lifetime for prosthetics and medical care.

Country Amputation Rate per population

Cambodia 1 per 236

Angola 1 per 470

Somalia 1 per 650

Uganda 1 per 1000

Vietnam 1 per 1250

Mozambique 1 per 1862

United States 1 per 22,000

Table 1: Amputation rates for mine affected countries and the United States.

According to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), those at highest risk of mine injury are the rural

poor. Peasants foraging for firewood and food, herding cattle, or tilling their fields are particularly at risk. Similarly,

when refugees and internally displaced persons return home at random and not as organized groups, they are at risk of

being killed or maimed from landmines because they return to areas that often have been involved in fierce fighting and

may therefore be heavily mined. They are also at high risk because they are less familiar with their former ”changed”

environment. In the case of some countries, young men and women return who were born in refugee camps and have

never seen their parents’ land before.

The ICRC has documented three patterns of landmine injuries based on data collected from multiple wars and

thousands of patients. Pattern I, usually the most severe on presentation, occurs after a person steps on a buried

APL. The injury usually produces a traumatic amputation with severe wounding of the contralateral leg, genitalia and

arms. The blast is associated with proximal muscle damage and secondary contamination with mud, bone, plant

material, plastic or metal fragments, and bits of clothing or shoes. (Figure 4) The level of damage depends upon the

amount of explosive and the size of the victim. Bilateral amputations have been reported in 5% to 10% of incidents and

orchiectomies in 1% to 2%. Of 720 patients with landmine related injuries seen at one ICRC hospital, pattern I injuries

accounted for 28% of patients.

Figure 4: Pattern I injury (ICRC)

Pattern 2 relates to injuries usually sustained from a fragmentation or anti-tank mine. The mechanism that

produces this injury pattern is similar to that of other fragmentation and shrapnel type weapons. These wounds can

effect any part of the body and patients frequently require intra-abdominal exploration for bowel injuries. These wounds

accounted for 50% of ICRC patients. Pattern 3 consists of wounds sustained while handling a mine either by a demining

worker or more frequently by children playing with small mines. These wounds cause injury to the hands and face, and

frequently cause blindness secondary to the blast.

A study on civilian landmine injuries in Sri Lanka found an incidence rate of 72 per 100,000, similar to the 50-120

per 100,000 from Mozambique and much higher than the 10 per 100,000 in Kosovo. Landmine injuries have also

been responsible for many wartime casualties. These weapons accounted for 30% to 40% of the trauma cases treated

by Soviet medical personnel during the war in Afghanistan. During the Vietnam War, 33% of all U.S. casualties and

28% of all deaths were officially attributed to mines.

In a household survey in Mozambique, Aschiero calculated a case fatality rate of 48% for landmine injuries. In Sri

Lanka, Meade reported a rate of 29%, 80% of whom were dead on arrival to the hospital. A study by Anderson, et al

calculated a case fatality rate of 30%, with 75% of those deaths occurring in the field. These figures are all significantly

higher than the hospital mortality rate of 3.2% reported by the ICRC from the war injury database. The difference in

rates can be explained due to the long transport time for patients going to ICRC hospitals and the fact that data on

victims who died in route were not recorded. In Mozambique the data included all injuries from a community sample and

the Sri Lankan study was undertaken in a limited catchement area where most victims were probably taken to a hospital.

Data from the ICRC studies shows that amputations occur in approximately 23-30% of landmine victims, however

amputation rates as high as 75%, 93% and 100% have been recorded in series from Afghanistan, Thailand and

Guantanamo Bay. Variations in the percentage of above versus below knee amputations have also been documented,

although the bilateral amputation rate seems fairly consistent. These rates may reflect a difference in treatment or other

variables including transport time or types of mines. Of interest, data from Thailand showed that victims wearing boots

had significantly higher amputation levels than those wearing sandals or sneakers, the boots may have transmitted the

explosive force further up the injured limb. All the studies showed that landmine victims on average require more

operations to care for their wounds and are at a high risk of needing multiple blood transfusions when compared to

victims of other war injuries.

Landmine victims are predominantly young males. When studies of civilian injuries are compared to those of military

casualties, not surprisingly, a greater percentage of women and children are included in the data.

The majority of landmine incidents occur to groups with more than one person injured at a time. Injuries and death

result from multiple missile fragments, the use of anti-tank mines that can destroy a vehicle with many persons or the

placement of multiple landmines in a confined area or trail. For example, in one incident from the Korean War described

by Captain Edward R. Hindman, “a divisional unit of company size was moving into (an) area when one man tripped a

Bouncing Betty. Immediately two other men rushed to his aid, and one of them tripped another mine, killing himself and

wounding the other. Other personnel tried to get to the wounded men, and more mines were set off. In a ghastly

debacle that lasted only a few short minutes, a total of sixteen men were killed and wounded by our own mines.”

Such scenarios have been played out repeatedly both with military and civilian victims. Minefields are designed to

place mines in a pattern that will inflict maximum damage. During conflicts, minefields are supposed to be mapped so

that afterwards they can be marked and cleared. However, maps are not always kept or accurate and minefields are not

always marked. The use of scatterable mines also complicates removal, as the exact location of the mines is difficult to

ascertain.

In addition to the physical injuries caused by landmines there are many indirect effects. According to Anderson,

between 25% and 87% of households in Afghanistan, Mozambique, Bosnia and Cambodia had daily activities affected

by landmines. The mere presence of a minefield can prevent access to safe drinking water, leading to an increase in

intestinal diseases, diarrhea and death. Landmines can also worsen iodine deficiency disorders in villages located in

iodine deficient areas by preventing access to food being transported in from iodine sufficient areas. The inability to

conduct vaccination or public health campaigns using mobile teams has also led to increasing rates of polio and

worsening health.

Landmine injuries themselves place an enormous burden on local communities. A mother killed or disabled by a

landmine is often unable to provide for her family, a child injured by a landmine often becomes a burden on its family,

health services and society in general. Countries most effected by landmines have also generally had their medical

infrastructure severely damaged by war. Landmine injuries require skilled surgeons, large amounts of blood, antibiotics,

prosthetic devices, and intensive physical therapy. A study of patterns of hospital utilization show that even if only 4% of

a hospital's admissions are landmine victims, they tend to utilize 25% of all surgical services and resources. In a

country where resources are already scarce, caring for landmine victims draws resources from other essential health

services and tends to worsen the health status of the entire population.

Loss of livestock is also another important aspect in mine affected regions that effects both the economic and

nutritional status of the population. In Libya between 1940 and 1980, an estimated 125,000 camels, sheep, goats and

cattle were killed due to landmines remaining from World War II. In Afghanistan 264,000 goats and sheep were

reportedly lost at a value of US$ 31.6 million. Anderson’s study recorded 54,554 animals killed representing a value of

US$ 6.5 million.

TREATMENT OF LANDMINE INJURIES

Victims and survivors of landmine injuries need to be transferred to sites where appropriate and safe definitive

treatment can be undertaken. Studies have shown that the number of trained surgeons in many developing countries is

limited and have indicated the danger of attempted treatment by unskilled practitioners. Data from the ICRC shows that

only 24.6% of landmine injured patients present to a hospital within 6 hours, with 70% presenting within 24 hours and

16% arriving more that three days after injury. These data help explain the relatively low hospital mortality of 3.2%, as

the sickest patients never arrive for definitive treatment.

These figures highlight the massive problem with transportation to medical facilities; however, they also underscore

the importance of resuscitation and transfer for definitive care. Much of the recent literature concerning the

management of war-related injuries presumes that modern and well-equipped facilities are available after rapid

transport. This assumption does not apply in many countries where forgotten landmines continue to menace the local

population. While rapid definitive therapy may improve the ultimate outcome, this is rarely an option. Sound surgical

judgement along with proper wound management will provide the best outcome; however, this is only possible if the

patient reaches the hospital alive.

The United Nations Mine Action Service has developed international standards for humanitarian mine clearance

operations. The purpose of this document is “to establish medical support standards for rapid resuscitation and

stabilization of the casualty and the prompt evacuation to a facility where emergency surgery can be undertaken.” This

document presumes that mine-clearing teams have access to rapid transportation and first aid medical assistance.

Most civilian victims of landmines do not have access to such luxuries. It is therefore necessary for local districts to

establish the means for providing adequate first aid and transportation to definitive care facilities.

PUBLIC HEALTH ISSUES AND THE FUTURE

In 1995 the General Assembly of the World Health Organization recognized that landmines were a worldwide public

health concern. Krug, et al outlined the need to address this problem from a public health perspective. Such a plan

would first determine the magnitude, scope and characteristics of the problem. The factors that increase the risk of

disease, injury or disability could then be studied to determine which were potentially modifiable. By using the

information about causes and risk factors, an assessment could then be done to prevent the problem by designing, pilot

testing and evaluating interventions. The most promising interventions could then be implemented on a broad scale.

Such interventions are already underway. Coordinating bodies such as UNMAS and the Geneva International Center

for Humanitarian Demining have begun a coordinated method of data collection on mine-affected countries and injuries.

Work by WHO and non-governmental organizations has been important in developing and pilot testing surveillance

systems in Uganda, Azerbaijan and Kosovo. Initial goals of improving data collection and providing a method to

document changes in incidents and relief for survivors is slowly progressing. The international community continues to

recognize the massive losses caused by these weapons. Many nations, with the United States as the leader, continue

to contribute millions of dollars to demining efforts and for victim assistance around the world. Only through prevention

and understanding will a coordinated effort be able to care for the thousands of landmine victims each year.